The truth is stranger and far better. There isn’t one hole. There are a few, and what waits at the bottom of each says a lot about the country above.

The cage door rattled shut and the light became the sort of darkness you feel on your teeth. We dropped fast, shouldering into warm air, miners joking about tea while the floor trembled in small, honest shivers. At 1.1 km down, the walls turned to salt — white, pink, translucent — and the mine felt like a man-made cathedral, carved out of a vanished sea.

Down here, science hides from the sky. The Boulby Underground Laboratory sits in the hush, listening for particles too shy to show themselves on the surface. The lift stopped with a bunker-thud, and someone nodded me forward into the glow.

There’s something else down there.

So which hole counts as “the deepest”?

When people ask this, they tend to mean one of three things: deepest mine you can ride into, deepest borehole drilled, or deepest natural drop. Each has its own winner, its own flavour of “bottom”. The answer matters, because the geology, the kit, and the risks differ wildly.

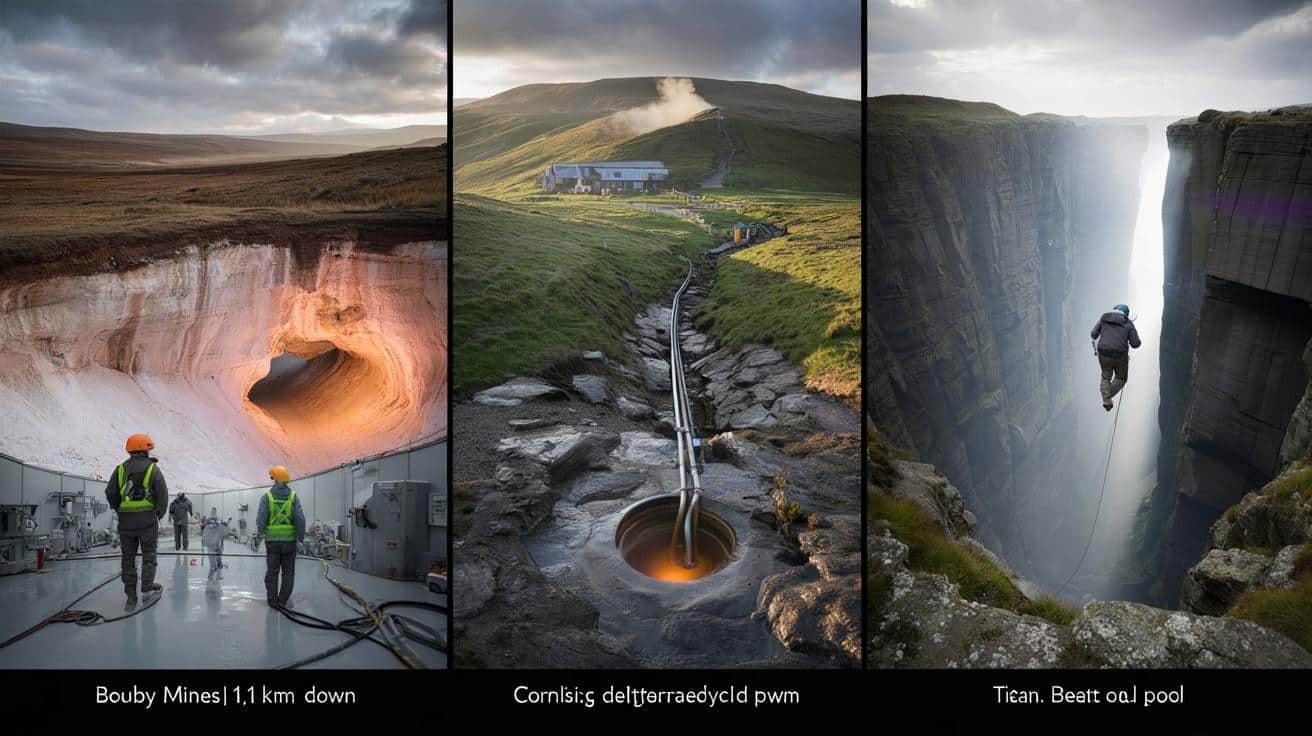

For the deepest mine, head to the North Yorkshire coast. **Boulby Mine** drops roughly 1,100 metres beneath the moors to the Permian salt beds. It’s an industrial labyrinth where polyhalite is cut from rock laid down by a 250‑million‑year‑old sea. Tucked inside sits the Boulby Underground Laboratory — a physics outpost shielded by a million times less cosmic radiation than the surface.

If we’re talking sheer depth drilled in Britain, Cornwall quietly holds the crown. The **United Downs** geothermal project pushed a production well to around 5.1 km, into hot, fractured granite. That’s not a cavern you can walk into; it’s a narrow steel‑lined bore sniffing out scalding brines. For a natural drop you can picture, the Peak District’s **Titan** is a single, dizzying shaft of about 141 m, linking into the Speedwell–Peak Cavern system. Different holes. Different “bottoms”.

What’s really at the bottom?

Here’s a simple way to picture it. Start with what your boots touch. In the mine, the “bottom” is a tunnel floor in salt and potash, warm and gritty, with a breeze that tastes faintly of minerals. In the borehole, the “bottom” is a set of pressure and temperature readings, a valve, data on a screen — the earth’s heat doing its quiet work. In the cave, the “bottom” is a boulder choke or a stream vanishing to a place your eyes can’t fit. Three worlds, one island.

Take a concrete example. Boulby’s deepest working levels feel like a salt city, with machines gnawing at rock that glitters under cap‑lamps. A few corridors away, the underground lab runs detectors and biolab rigs in a low‑radiation pocket, hunting rare signals and testing life‑detection tech. In Cornwall, the United Downs wellhead sits in a fenced compound on a windy hillside, pulling up hot, mineral‑rich water from granite around 180–190°C far below. Peak District cavers who descend Titan drop into a dark amphitheatre, rope humming, to land on a sloping floor where water prises open the limestone grain by grain.

Geology explains why each bottom looks the way it does. The North Sea’s retreat left thick Zechstein salts beneath Yorkshire; salt is plastic and dry, perfect for mining and for physics that needs quiet rock. Cornwall’s granite holds heat like a bank account — drill deep enough and you tap the interest. The Peak’s limestone lets water carve its own elevators, shafts and sumps pointing toward rivers that sneak out miles away. *A bottom isn’t just a depth. It’s a story about time, pressure, and water on the move.*

How to separate myth from ground truth

Use the triangle: depth, access, purpose. If a claim says “deepest hole”, ask three things. How deep in metres? Can a person go there, or is it a steel tube? What was it dug for — mining, energy, exploration? That triangle turns rumours into facts in under a minute, and it helps you compare apples with apples.

Common traps? Mixing “measured depth” in drilling (which can include long horizontal sections) with true vertical depth. Confusing a mine’s deepest shaft with the deepest working face. Calling a cave bottomless because it swallows your torch beam. We’ve all had that moment when a simple question sends you down a rabbit hole; breathe, pick one definition, and carry on. Let’s be honest: nobody rappels 400 feet into a cave on a random Tuesday.

“At the bottom you don’t find monsters,” a mine engineer told me, grinning under a salt-dusted helmet. “You find data, and you find heat.”

- Boulby bottom: a salt-and-polyhalite workplace and a low-radiation lab listening for faint signals.

- United Downs bottom: a 5 km‑deep granite fracture zone, brines hot enough to scald, pressure controlled at the surface.

- Titan bottom: a boulder slope and streamway feeding the Peak–Speedwell system, cold, echoing, alive with drip and time.

Is there anything surprising down there?

The surprises are small and human. In the mine, it’s the way white salt walls glow peach under sodium lights, and how your sweat dries oddly fast. In the lab, it’s the hum of instruments that exist because the planet itself is a shield. In Cornwall, it’s the smell of hot damp air near the separators, a reminder that the UK has deep heat in its bones. In the caves, it’s silence with edges, broken by water gossiping in the dark.

| Key point | Detail | Interest for the reader |

|---|---|---|

| — | The UK’s “deepest hole” depends on definition: mine, borehole, or natural cave. | Helps you win arguments — and understand three very different underground worlds. |

| — | Boulby Mine reaches ~1.1 km; United Downs well ~5.1 km; Titan shaft ~141 m. | Concrete numbers to map the mystery onto real places. |

| — | Bottoms aren’t empty; they hold salt cities, hot brines, and rivers in the dark. | Turns a headline curiosity into vivid images you can almost feel. |

FAQ :

- Is Boulby really the deepest place you can go in the UK?As an accessible, ride-the-cage experience, yes — around 1.1 km down into the salt. Deeper points exist in drill holes, but those aren’t human‑scale spaces.

- What’s the deepest hole ever drilled on UK soil?The United Downs geothermal production well in Cornwall is among the deepest onshore, at roughly 5.1 km, tapping hot fractured granite for heat and power trials.

- What about the deepest natural cave?Britain’s deepest cave systems are in Wales and the Dales; Ogof Ffynnon Ddu in South Wales reaches over 300 m of vertical range. For a single pitch, the Peak District’s Titan drops about 141 m in one go.

- Can the public visit any of these “bottoms”?You can tour show caves like Peak Cavern and join special winch meets at places like Gaping Gill. Boulby is a working mine and lab with limited access; Cornwall’s wellheads can be seen from outside, with occasional open days.

- What’s actually at the very bottom — treasure, fossils, anything wild?No treasure chests. You’ll find ancient salt layers at Boulby, instrument strings and hot brine at United Downs, and water‑cut passages or rock chokes in caves. The wonder is in the age, the physics, and the fact that Britain’s deepest places are quietly busy with work.